De-regulating the wheat market without breaking the system

Wheat reform will not work through fiat or faith. It needs coordination, credibility, and commitment.

Reforms collapse when treated as shock therapy. Sequencing matters. You do not float the currency before anchoring inflation, you do not dismantle procurement before building price benchmarks, and you do not yank liquidity before fixing risk architecture. Every system has interdependencies; pull one lever without preparing the others and you set off a chain of unintended consequences that inadvertently land us back in crisis mode. Real reform is not about speed, it is about choreography: sequenced steps that build institutional capacity and stakeholder buy-in, so the transition holds instead of imploding.

Why wheat matters

Because it feeds the country, but for decades has also been feeding fiscal disasters.

Since the 1960s, Pakistan’s wheat market has relied on a fragile three-legged stool: minimum support prices (MSPs) to reassure farmers, public procurement to mop up surpluses, and flour subsidies to calm urban voters.

The old model relied on:

The system was supposed to be politically expedient; instead, it has proven to be economically ruinous. Prices were set by decree, not supply and demand; storage leaked; carrying costs ballooned; and informal actors filled the vacuum left by a dysfunctional state system.

That era is now over.

Budget constraints, IMF program conditions, currency instability, and climate volatility have forced the hand of policymakers to finally unhook wheat from the state’s balance sheet. But timing and sequencing are everything. Move too fast, and we trigger panic. Move too slow, and we stay trapped in debt, distortion, and dependency.

This note outlines how to exit the old model without detonating the system.

The Big idea: liberalize the wheat market without creating mayhem

NCGCL’s big idea is to put the private sector at the center.

Instead of the government buying wheat and stockpiling it at significant costs that are ultimately borne by the taxpayer, the reform pathway replaces state procurement with private sector-led contracting and financing:

Key steps in the new model:

- Buyers [whether mills, traders, exporters etc] commit to pre-agreed forward contracts with farmers.

- Banks finance these purchases using the contract as collateral.

- NCGCL provides a credit guarantee against the contract to de-risk the loan, not the commodity price risk.

- Buyers deposit <7 percent of contract price in an escrow to prove they are not bluffing.

- If the buyer defaults, the escrow compensates grower for any losses resulting from distressing selling at spot prices

- No grain changes hands (delivery) until harvest. No state-managed storage and warehousing. No MSP.

A phased transition from price-fixing to price signaling. Underwritten by trust, not the treasury.

Why this reform is urgent

Because all the old crutches are gone.

- Fiscal space is exhausted. There is no more money to buy wheat or subsidize flour.

- IMF conditions have shut the door on “off-the-books” borrowing to fund support prices and procurement.

- Climate shocks are disrupting yields with increasing frequency.

- Currency stability is fragile. Import dependence poses a tail risk to forex reserves.

- Global food commodity markets remain volatile. Food inflation risk is real.

- Rural economy needs reassurance. Farmers failed to hit break-even on their wheat output for last 2 years, and may significantly cut back on cultivation & investment if not offered visibility on their path to profitability next year

With the public sector no longer willing to underwrite wheat production, the floor has quite literally vanished from under the rural economy. Farmers are losing trust. If the state won’t buy, and the market cannot signal, they simply won’t sow (or switch to competing, ‘safer’ alternatives).

This is not just a moment for reform. It is the last safe exit before the crash.

Won’t deregulation increase price volatility, worsening food insecurity?

Only if we botch the transition.

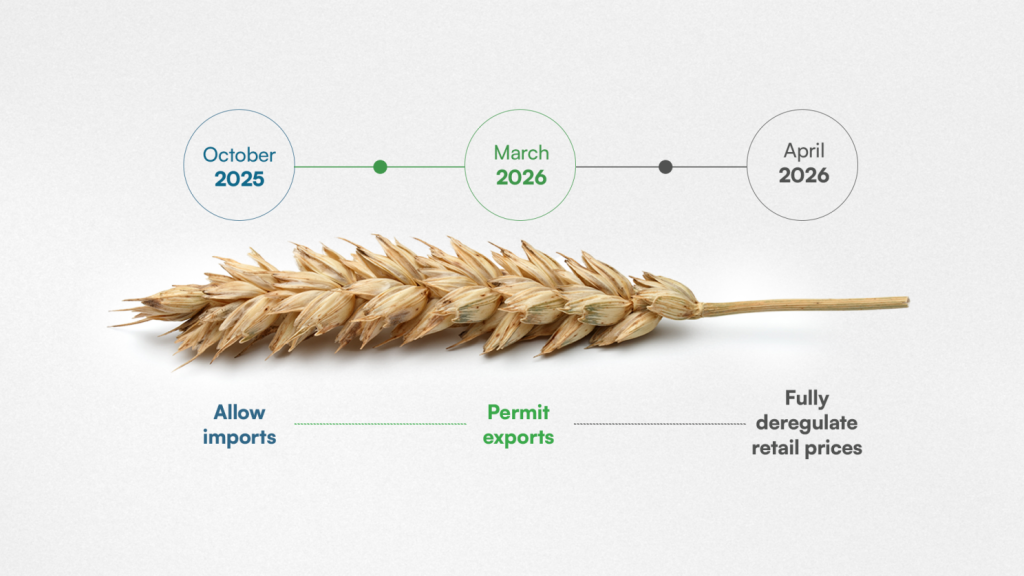

Wheat prices in Pakistan already follow global trends, just with a lag. Historically, exchange rate movements explain 35 to 40 percent of domestic price variation. That means, if we sequence trade flows smartly: permit commercial imports beginning October 2025 (when off-season demand begins to peak), while deregulating exports fully beginning March 2026 (when the next harvest shall begin), market will find its own floor and ceiling. This should be followed by deregulating consumer end prices beginning April 2026, and retail prices shall find their equilibrium.

But the path to this transition must be publicly declared now. Markets function most efficiently when they have confidence in future. If these announcements are delayed or reversed mid-season, any exogenous shock – such as from an extreme weather event, global commodity markets, or currency volatility – will inadvertently lead to hoarding, under-planting, and panic.

Liberalization may or may not deliver cheaper prices. But excessive, heightened uncertainty will guarantee a crisis of food insecurity.

Can the market stabilize without a minimum support price?

The MSP is now history. But a floor need not be.

The MSP was the state’s way of saying: “We will buy your produce, no matter what.” That blank check is no longer viable. But the market does not need MSP to signal certainty. It needs forward visibility and contract enforcement.

Hence the replacement model:

- Buyers (mills, traders) issue forward contracts for guaranteed purchase to farmers ahead of sowing.

- The price is pegged to expected FX-adjusted parity for the harvest window (April–June 2026).

- Banks lend against these contracts. NCGCL guarantees the loan, not the commodity.

- Escrow margin (<7 percent of contract value) ensures buyer commitment.

- If the buyer defaults on contract fulfillment, the escrow compensates the farmer, even if spot price crashes during peak harvest months.

- If the buyer fails to make the bank whole due to adverse price movement post drawdown, NCGCL covers the bank’s credit risk.

Result: a market-driven floor price that does not bankrupt the state.

The MSP’s unconditional state purchase guarantee will be replaced by a market-driven floor created through private contracting. Instead of relying on state procurement, forward contracts will set prices pegged to expected FX-adjusted parity for the harvest period.

Banks may lend against these contracts, with NCGCL providing guarantees that cover credit risk rather than commodity price risk. Escrow margins ensure that buyers have a real stake in fulfilling their commitments and will compensate farmers in the event of default. This approach gives farmers certainty without burdening the exchequer.

NCGCL’s Role

NCGCL will serve as the system’s risk buffer, ensuring that contracts function as intended. By absorbing the credit risk, it inspires confidence between market players where there was none before:

- It guarantees repayment only after financing is drawn and buyer defaults.

- It does not guarantee wheat prices, retail margins, or volumes.

- It prevents abuse by ensuring only credible, financed contracts qualify for the guarantee.

- It exits if the buyer walks away pre-financing, while making the producers whole using the margin held in escrow.

Think of NCGCL as the circuit-breaker between market confidence and system risk. It keeps the wheel turning without becoming the axle.

Why Escrow Matters

It separates genuine investors (buyers) from the noise (the speculators).

Escrow deposits, set at roughly seven percent of the contract value, are central to separating genuine buyers from speculators. This margin ensures buyers have skin in the game, discourages default, and provides direct compensation to farmers if a buyer fails to purchase post-harvest. If a buyer exits the contract early, the deposit is returned (minus any administrative costs). In combination with NCGCL’s guarantees, escrow arrangements can make it possible to replace MSP with enforceable, market-based commitments.

Government’s new role

The government can finally move away from acting as the dominant buyer and instead focus on regulation, market oversight, and policy signaling. Its responsibilities will include setting and enforcing clear rules on imports, exports, and wholesale/retail price deregulation, as well as ensuring contract transparency and enforceability.

For this to happen, it must formally lay out a policy plan by September 2025:

- that there will be no public procurement for the 2026 harvest.

- that commercial imports – and not those underwritten by TCP – will be allowed beginning October 2025.

- that exports will be permitted beginning next harvest season in March 2026.

- and that wholesale/retail markets prices shall be fully deregulated from April 2026.

These announcements must be irreversible and backed by the full authority of the state to avoid market uncertainty.

Otherwise, we shall sleepwalk into yet another procurement fiasco next April.

Infrastructure Gaps

This means market infrastructure must improve:

- Certified warehousing currently covers less than 20 percent of the output.

- Mandi and crop data remains opaque

- Contract enforcement systems are underdeveloped.

Parallel investments are needed in:

- Price transparency through encouragement of derivatives trading at commodities exchange

- Certification and accreditation of warehousing and stored produce through collateral management companies.

Risk of poor execution

Delays in announcement, weak signaling, or policy reversals will:

- Trigger hoarding and artificial scarcity.

- Discourage planting, reducing national output.

- Add 1.5–2 percentage points to CPI through retail level price inflation.

- Delay the benefits of market reform by at least one full crop cycle.

Predictability is not a nice-to-have. It is the reform.

What success looks like

Success will mean a wheat market in which floor prices arise from private contracts rather than state-set MSPs, and financing flows are based on credibility rather than political discretion. The state will provide stability and transparency without overshadowing private enterprise, and annual emergency procurement cycles will no longer be necessary. A predictable, self-regulating market can emerge, guided by clear rules and credible commitments.

Conclusion: To let the market breathe, give it oxygen first

- This is not about shrinking the state. It is about getting out of the way, without walking off a cliff.

- Announce early. Signal clearly. De-risk selectively. Then step back.

- Wheat reform will not work through fiat or faith. It needs coordination, credibility, and commitment.

- The good news? The tools exist. The bad news? The window is closing.

- The choice is simple: fix the system, or stay in firefighting mode perpetually.